From her building in 1905 by Colin Archer, the celebrated Norwegian naval architect, to her pivotal role in the 1914 Howth gun-running and her later use as Ireland’s first national sail-training vessel, Asgard has had many incarnations.

This article deals with the birth of Sail Training in Ireland, from the 1905 Gaff Ketch Asgard, through the 1963 Bermudan Ketch Creidne, and up to the Asgard II Brigantine and her subsequent loss in the Bay of Biscay. It also will cover the characters and adventures in the early years of Sail Training in Ireland and will be regularly updated as new facts emerge or adventures, stories and information is submitted.

Like so many of us in Sail Training today, we were inspired to embark on careers at sea, and the Asgard story is personal and holds a very special place in our lives. In March 1970, I sailed for the first time aboard Asgard from Dun Laoghaire with Skipper Eric Healy as a teenager, and it set me on a path for life.

Throughout this site and in our literature, we have tried to get across the point that Sail Training is not about learning to sail! The big insights come from within, we learn about ourselves, we learn resilience and self-development and somewhere in there we learn about ships and gain a love for the sea. Its for everyone, all ages, genders, backgrounds and challenges thrive in a tall ship environment.

In every aspect of my life all that I learned through the three Irish sail training ships has been a central influence. Today, working with the Atlantic Youth Trust, I meet people is all sorts of places who have told me the same story. How Asgard has given us such a firm foundation for our lives. The thousands of Asgard crews continue to spread the word. There are so many stories to share, and we’d love to receive your personal journals or experiences to put here on this site. These inspiring stories help us to tell the most important one, how we make sure that young people get the same opportunities.

Ireland today, in many instances, has it’s back to the sea so to speak; we are an island and there is such a variety of opportunity to be had in the maritime industries today and yet there remains shortages of young seafarers. With the work of the NMCI (National Maritime College of Ireland), BIM (Bord Iascaigh Mhara), The Nautical Trust and Sail Training Ireland this is changing. We, in the Atlantic Youth Trust, are working together with these organisations to enable this change and rekindle the spirit of Asgard.

I have drawn on texts from the national Museum of Ireland, Afloat Magazine and the definitive history of Asgard by W.M. Nixon, from personal memory and other sources. I would love to hear your stories and experience aboard all three vessels and please email them to [email protected]

Asgard: The Story of Irish Sail Training by Nixon, William M., Healy, George Frederick (ISBN: 9780953812509) from local books shops and from Amazon’s Book Store.

This is an amazingly detailed and complete history, and I thoroughly recommend it to all Asgard enthusiasts who may not have already bought is.

Many Black & White photos I took as a teenager aboard Asgard in the early years. The authors did a magnificent job.

There is no better reference volume on the Asgard years than this book. It’s astonishing how much detail and how accurate (from personal experience) it is covering every aspect of Asgard’s history. This book is the best place to start.

Many of the stories and great characters of the Asgard years are here. Photographs on pages 83 and 97, for example, I took as a 16-year-old (amateur photographer- developed and printed) on different voyages and they languished in a cardboard box Skipper Eric Healy’s house until reproduced here in 2000 by W.M. Nixon. Seeing them and reading it all again for this article take me back many years and I recall the great people who were the foundation and inspiration for Sail Training in Ireland.

In addition to this book, I have tried to add details and stories not written elsewhere and have also compiled articles and extracts from websites to paint a history of the Asgard years.

Since August 2012 the Asgard has been on display in Collins Barracks. She stands as a monument to the skill of both the original builders and the conservation team, as well as a reminder of the turbulent events of 1914.

After successfully landing her cargo of guns and ammunition at Howth harbour on 26th July 1914, Asgard’s dramatic gun-running voyage was over. She sailed out of Howth and across the Irish Sea to Bangor, North Wales, where she was laid up in the boatyard of A. M. Dickie & Sons. She would remain in storage there until 1927, when Molly Childers was finally persuaded to place her beloved yacht on the market. Asgard was sold in 1928 and would have three further owners before being purchased by the Irish Government in 1960 as a training vessel for naval cadets.

ollowing a refit to make her seaworthy, Asgard sailed on a historic voyage from Southampton to Howth, arriving on 30th July 1961. At Howth she was met by Naval Service vessels, a salvo of guns and a welcoming group led by then President Eamon de Valera, as well as by surviving Irish Volunteers who had witnessed Asgard’s original arrival at Howth in 1914.

The ceremony was also attended by Erskine Hamilton Childers, son of Erskine and Molly and a future President of Ireland. President de Valera sent greetings to Molly Childers, then living at Glendalough, and ended his speech with the words:

“The great event of forty-seven years ago, in which she and her gallant husband took so memorable a part, will never be forgotten by the Irish people.”

The refitted Asgard served as a sail training vessel and took part in international tall ship events.

Over the succeeding years the Asgard saw some use as a navy cadet training vessel, but there was speculation over her future. Maintenance costs were high, and the vessel spent much time in dry dock. The idea of preserving her as a museum ship was suggested at this stage but was opposed by those who wished to see the ship preserved as an operational vessel.

In 1968 responsibility for the ship was transferred to the Department of Finance. It was confirmed that the vessel was to remain afloat serving as Ireland’s first civilian sail training vessel. To manage the ship in its new role a committee of experienced yachtsmen was established.

The vessel then underwent a refit in which the interior was modernised to meet the needs of a crew of trainees, while the cockpit was replaced with a wheelhouse which offered better protection from the elements. She was then placed under the command of Eric Healy who would remain her captain throughout her service as a training vessel.

Over the following six years the Asgard served as a training vessel and racing yacht. Over 1,500 trainees had the opportunity to sail her during these years. She also took part in international tall ships events where she performed well, winning several races over the years.

Those who sailed the vessel during these years have fond memories of the experience. The historical importance of the vessel combined with the fact that it offered the only real opportunity to experience life aboard such a ship were the main attractions.

The details of life aboard ship were perhaps less appealing. The vessel usually sailed with a compliment of about 13, which included the Captain, Eric Healy, 3 or 4 experienced yachtsmen who would act as watch officers and watch leaders, and 7 or 8 trainees. Often the Watch Leaders were trainees who had come through several voyage and who knew Asgard well.

This made for a cramped living space where one member of the crew would have to sleep on the chart table. Added to this the sleeping area was very damp as the old hull leaked badly.

But as teenagers we didn’t much mind and we survived and thrived with adventure of it all.

I think the concept of Youth Development through Sail Training was not much spoken about in the way it is today, but it was a central philosophy of Eric Healy our Skipper. The opportunities and the openness of the scheme, the way he encouraged diverse crews of both genders, and he made sure we all did every job and had every opportunity that came from life aboard a tall ship was there. It was the making of so many of us and the inspiration for our future. We learned independence, cooperation, resilience and self-esteem and that was a real starting point. There is perhaps more social science about it these days, but the ideas were there from the start.

Then in late 1973, the year I left school, it was announced that the Asgard would be replaced by a new larger vessel which could take part in transatlantic racing. Credine would be a temporary replacement until the new ship was ready. Credine was a worthy successor and fulfilled her role admirably in the intervening years.

Years of neglect followed until in April 1979 she was put on display in the grounds of Kilmainham Gaol Museum, here’s the story of her final voyage.

This is taken from an excellent article by John Kearon of Arklow from Classic Boat (Edition CB244) where John explains how Erskine Childers’ famous gun-running yacht, Asgard, and icon of Irish independence is being restored for display.

Following a decade of debate on whether she should be conserved ashore or restored and return to sail, Asgard is slowly (and lovingly) being conserved in Dublin.

What finally won the debate was acceptance by most involved that Asgard was predominantly original in her structure and given her iconic stature and importance in Irish history should be conserved for indoor display.

Restoration to sail would result in a virtual replica, with little or none of the original saved.

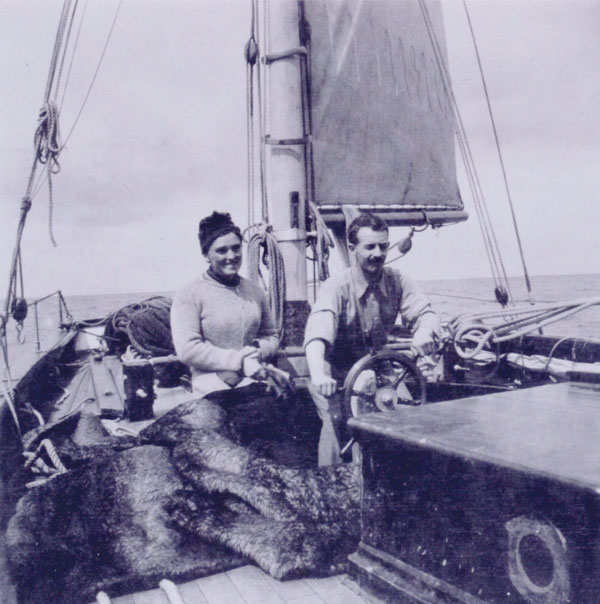

Asgard’s importance has several aspects: in Ireland it is the historic gun-running voyage in 1914 when Erskine Childers, with his wife Molly and some friends, brought arms and ammunition into Ireland that were used in the 1916 Easter Rising. Then there is her pedigree through Colin Archer, her Norwegian designer and builder, who also designed and built the polar expedition ship Fram, preserved and on display in Oslo.

There is also The Riddle of the Sands, Childers’ classic espionage novel which most who sail have read for its brilliant descriptions of sailing in hazardous waters and, after 105 years has never been out of print. Lastly, there is Childers himself – superb yachtsman, war-hero, patriot, secretary to the 1922 Treaty negotiations and ultimately a martyr (shot in 1922) in the struggle for Irish independence – the man inextricably linked with Asgard.

Managing the conservation of such a vessel carries a particular responsibility, not least that of applying museum standards of conservation on a large and, in all honesty, old and degraded wooden yacht. Asgard is a sturdily built yacht: very much a Colin Archer. Built in Norway in 1905, she measures nearly 51ft (15.5m) in length, with a beam of 13ft (4m).

Construction is carvel, of oak (topsides) and pine (underbody) on sawn double-frames. The frames are of Scots pine, which would be considered unusual in the British Isles, but common in Norwegian built vessels. They alternate with bent oak timbers.

Restoration to sail would result in a virtual replica, with little or none of the original saved.

Asgard’s importance has several aspects: in Ireland it is the historic gun-running voyage in 1914 when Erskine Childers, with his wife Molly and some friends, brought arms and ammunition into Ireland that were used in the 1916 Easter Rising. Then there is her pedigree through Colin Archer, her Norwegian designer and builder, who also designed and built the polar expedition ship Fram, preserved and on display in Oslo.

There is also The Riddle of the Sands, Childers’ classic espionage novel which most who sail have read for its brilliant descriptions of sailing in hazardous waters and, after 105 years has never been out of print. Lastly, there is Childers himself – superb yachtsman, war-hero, patriot, secretary to the 1922 Treaty negotiations and ultimately a martyr (shot in 1922) in the struggle for Irish independence – the man inextricably linked with Asgard.

Managing the conservation of such a vessel carries a particular responsibility, not least that of applying museum standards of conservation on a large and, in all honesty, old and degraded wooden yacht. Asgard is a sturdily-built yacht: very much a Colin Archer. Built in Norway in 1905, she measures nearly 51ft (15.5m) in length, with a beam of 13ft (4m).

Construction is carvel, of oak (topsides) and pine (underbody) on sawn double-frames. The frames are of Scots pine, which would be considered unusual in the British Isles, but common in Norwegian built vessels. They alternate with bent oak timbers.

And therein lies the problem: interaction between differing metals in a salt-laden environment. Brass, iron, steel and zinc all in close proximity, effectively hundreds of active batteries with the lesser metals (iron, steel and zinc) becoming the anodes to the cathodic brass – and seawater providing the electrolyte.

The vessel is riddled with corroded iron and steel fastenings and fittings, all of which have affected the adjacent wood. The large iron keel bolts are also extensively corroded and have proved extremely difficult to draw out.

Some might expect no further corrosion with the vessel out of the water and dry indoors.

If only it were so simple! Analysis of a selection of steel hull fastenings by David Watkinson, head of conservation at Cardiff University, and an expert on corrosion, found that “the steel nails are highly unstable and contain significant amounts of chloride; are actively corroding and will continue to corrode in the mid-range relative humidities that suit the physical stability of wood”.

In other words, an ideal environment for Asgard’s wooden structure will cause corrosion to continue. The presence and effect of chloride in iron is a relatively recent concern where historic vessels are concerned. It is the main problem in both the Cutty Sark and the SS Great Britain and undoubtedly also in other old ships. Asgard may be the first wooden vessel where its presence in hull fastenings has been identified specifically for the destructive catalyst it is.

It became clear that in order to stabilise the vessel and protect her in the long term, all iron and steel fixtures and fittings would have to be removed. To leave corroding metal in place would, over time, result in their total mineralisation, further destruction of surrounding wood and massive damage to structural integrity.

If we were restoring Asgard to sail instead of conserving her, we would just pull the old planks and their fastenings off, remove the corrosion-damaged frames and renew both planking and framing. But, given the extent of corrosion-damaged components and the need to meet marine safety and insurance standards of seaworthiness, that would lead to the destruction and loss of her original structure and result in a virtual replica. This is the fundamental difference between restoration and conservation where original structures are involved.

One destroys in order to ‘save’, the other saves without destroying. Our basic approach to conserving as much of Asgard’s hull structure as possible is to remove the planking and damaged frame sections, causing minimum damage in the process; then to repair and consolidate them while retaining fundamental integrity. However, as any shipwright will agree, removing boat-nail fixed planks from large wooden vessels usually results in the destruction of the planking.

After considering several methods for removing hull planking relatively intact we decided on using small engineers’ hole-saws, which come in a variety of diameters (we use 17 and 20mm diameter) and by lucky coincidence come in a length just right for the thickness of Asgard’s planking. Using the planks’ countersunk fastening holes as a guide we bore around each fastening to the thickness of the plank; effectively removing damaged wood immediately around the nails. With all fastenings in a plank section bored, the plank can then be lifted off the nails, leaving them to be pulled out separately quite easily.

We then core out the holes from the inner face of the plank with a cone bit. This rids the holes of most of the degradation caused by corroded fastenings – rust in moist wood travels along the grain. Then we glue wooden cross-grained cone plugs into each hole, using a urea-formaldehyde wood adhesive, and plane them flush.

Badly damaged areas of planking may need localised repairs such as wooden inserts fitted; damaged and degraded butt-ends and hood-ends of planks may be cut back and have new wood scarphed on to form strong well-fixed ends. One particular repair involved the plank section through which the wing propeller shaft protruded.

Given that the vessel was built without an engine, the one fitted later, and its shaft became surplus to requirements. The large and damaged shaft hole area was sawn out of the plank and a new piece of wood scarphed in.

The frames are affected both by corroding nails and frame butt-straps. Corrosion damage around the butt-straps can be extensive, given the surface area of the straps and fastenings. In consequence, frames require a greater replacement of material than hull planking. Fastening holes in the frames are drilled out to remove rust residue and degraded wood and are then plugged with glued wooden plugs. Butt-strap corrosion damage can be dealt with either by scraping down to sound wood or by cutting away badly damaged wood and scarping and gluing inserts. The iron straps are then replaced with brass straps, through-fixed with copper round bar riveted over brass washers. The intention is to replace all ferrous material with silicon bronze, brass or copper fastenings and fittings.

One thing is clear: had the approach with Asgard been that of restoration to sail, then in certainty all planking and framing would have been lost, such is the extent of corrosion-induced damage. It is much greater than first realised – as became

obvious when separating mating surfaces and gaining full access to areas behind beam-shelves and stringers and when parting the large double floors and futtocks.

We are now at a stage in the project when we are not just removing planks and frames but beginning to put them back. However, an enormous amount of work remains to be done, not least the completion of the hull consolidation. Then we must recreate the accommodation, the coachhouse and companionways, as well as refurbishing the masting and rigging. Even the vessel’s dinghy will be recreated.

The original deck beams and deck planking will also need careful handling and treatment. The kauri pine deck was iron nail fastened and similar corrosion problems to the hull planks exist. It was difficult to convince people during the period of debate on the vessel’s future that the deck was original. One view put forward was that the aftermost deck-beams were not original and consequently neither could the deck be. On this point I will say thank heaven for graffiti-writing shipwrights!

Crawling in desperation to the aftermost beams, hoping to find some evidence to prove the beams were original, I found written on the after face of a beam in faded pencil: “Pall Gunlarson, Lawrvik, 1905”.

The Colin Archer Museum in Larvik were able to confirm that the writer was a shipwright that worked in the Archer boatyard at the time Asgard was built. The project is greatly assisted by a body of research that includes the original correspondences between Erskine Childers and the builder Colin Archer – a fantastic archive of detail that included Archer’s hand-written Asgard specification.

A collection of photographs taken on the yacht between 1906 and 1914 also help in the accuracy of reconstruction of that which is missing. But the entire vessel helps – her structure and markings and different woods give inherent evidence of past alterations and additions but also the evidence of original structures. We record every aspect of work done; with locations of new wood detailed on plank expansion and frame section plans. Likewise, a project diary of all works and methodology is recorded with both still and moving images.

The issues that surround Asgard apply to most vessels deemed significant and will strike a chord among all that care for unique and historic craft. Asgard is suffused with history and has survived with a hull that is approximately 90 per cent original. During the conservation programme that proportion will shrink a little with the necessary removal of badly degraded wood.

But at its end Asgard will have the great majority of her original structure intact.

Not bad for a much-used 105-year-old wooden yacht. Once the work of conservation is completed, she will be displayed in her original built form with her masts and rigging in place – the central focus in a magnificent gallery in the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin.

John Kearon, project manager on the Asgard Conservation Project, first became involved with Asgard in 1993 when he was with National Museums, Liverpool through a request to survey her from National Museum of Ireland (NMI).

Contact with NMI continued in relation to Asgard and more recently through another historic vessel in NMI’s collection. The French Admiral’s barge of 1796, known as The Bantry Boat, is the vessel on which the Atlantic Challenge Foundation is based, and like Asgard is a unique wooden boat linked with a troubled period of Irish history. Involvement in Asgard’s conservation was a natural step following his retirement from NML in 2006.

In his younger days John had served his apprenticeship in wooden boatbuilding and draughtsmanship with Tyrrell’s of Arklow who subsequently built the brigantine Asgard II, which carries on the Asgard name as Ireland’s national sail training vessel. His team includes shipwrights Brendan Tracey, Oliver Ward and John Proctor (who were also central to the building of Asgard II) and the youngest craftsman, Patrick Kirwan.

At last, in March 1981, the brigantine “Asgard II” was commissioned and Irish Sail Training had a worthy ship to carry on the name and bring young people to sea. Designed and built in a great tradition of sail by Jack Tyrrell in Arklow, she looked magnificent.

In 1968 the committee “Coiste an Asgard” was founded by the Irish government to organize sail training for the youth of Ireland, first they used the Colin Archer ketch “Asgard” between 1969-74, the ship was given to the Jail Historical Museum in Kilmainham in 1979.

In March 1981 the brigantine “Asgard II” was commissioned as a training ship for the Republic of Ireland.

The owner is the Dept. of Defence of Ireland; operator is the committee “Coiste an Asgard”.

Offers short cruises for adults during the spring and autumn but is otherwise used only by young people on voyages lasting about 1 to 2 weeks, visited the American East coast in 1985 and was carried on a freighter to Australia to participate the Race from Hobart to Sydney in 1988.

Has participated very successfully in many regattas, taking second place in the AII class at the 1986 Newcastle-Bremerhaven regatta, second place in the CII class at the 1996 Baltic Sail in the Rostock – St. Petersburg race and winning the race from Turku to Copenhagen, awarded the Cutty Sark Trophy for the ship’s crew who have contributed the most towards international friendship and understanding.

She offered accommodation for 21 persons – the young people perform 3 watches, each with an experienced duty officer.

The figurehead of the 16th Century warrior queen Grainne Mhaol provides a reminder of English Irish history.

The name “Asgard” is an old Norse word meaning “Home of the Gods”.

On Sept. 11, 2008 although in good weather conditions the ship sunk southwest of Belle-Île-en-Mer at the French coast, all crew member remained unviolated and were saved by the French coast guard, reasons for the sinking are not clear, in February 2009 was decided that the ship cannot be raised from the seabed because of too much costs.

Atlantic Youth Trust CLG is an Irish registered charity, which exists to build life skills, resilience, and co-operation in youths across the island of Ireland through the challenge of the sea.

Connecting youth with the ocean and adventure.